last updated: 4/2025

Amnesty International Korea owns all intellectual property rights in relation to the information and content of the interviews. You are asked not to publish or reuse any part of the content, with or without adaptations before obtaining written consent from Amnesty International Korea.

Surveillance in North Korea

Surveillance in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea exists solely to maintain regime stability. With no blind spots, surveillance permeates every aspect of society and daily life. Deeply embedded into people’s lives, it completely erodes personal privacy. Surveillance begins from birth and continues until death. Questioning this omnipresent surveillance is virtually impossible, as most people simply accept and conform to it. North Korean authorities view surveillance as an essential tool for maintaining social control. By identifying potential threats to state security beforehand, authorities aim to prevent any risks or dissent from surfacing. However, the indiscriminate nature of inspections and censorship against residents results in numerous human rights violations, including suppression of freedom of expression and invasions of privacy. Consequently, North Korea is aptly described as a “controlled society, “where surveillance is accepted as an unavoidable norm. The surveillance infrastructure in North Korea is more elaborate and systematic than in any other country, primarily relying on mutual monitoring among residents. At the lowest administrative level—the People’s Unit—leaders closely watch their neighbours. Mandatory organizations, such as the Women’s League, Youth League, and workplaces, conduct weekly Life Review Sessions, where participants engage in compulsory peer criticism, requiring individuals to monitor and report on each other’s behaviour. In addition to mutual monitoring among residents, North Korean state institutions conduct surveillance extensively. The Ministry of State Security (MSS), North Korea’s primary intelligence agency responsible for domestic surveillance, evolved from the Social Security Office, originally tasked with maintaining social order and public safety. The MSS now operates as a supra-legal entity specializing in political surveillance and counterespionage activities against anti-state, anti-Party, and anti-socialist elements. MSS officers personally conduct inspections and recruit residents to monitor local activities and report any dissent or suspicious behaviour. These co-opted residents act as MSS operatives, observing their acquaintances both openly and covertly. MSS branches exist in every province (do), city (si), and county (gun), with agents stationed even in towns (eup), neighbourhoods (dong), and villages (ri), maintaining constant daily contact with residents. Furthermore, surveillance networks extend to any gathering place, including workplaces and schools. Agents from the MSS not only conduct direct inspections but also recruit trusted individuals from the general population within their designated areas through bribery or coercion. These recruited informants are tasked with monitoring residents’ activities and reporting individuals suspected of harbouring “anti-state, ” “anti-Party, ” or “anti-socialist” sentiments, whom the authorities label as “impure elements.” Under MSS instructions, these informants observe those around them, both openly and covertly. How, then, are ordinary North Koreans monitored, and what does everyday life entail under constant state surveillance? Below is a condensed testimony from an individual who escaped North Korea, interviewed by Amnesty International Korea (AI Korea), providing insight into the daily reality of living under systematic government surveillance.

NAME: C. Y. S.

GENDER: MALE

YEAR OF BIRTH: 1960S

HOMETOWN: RASON

OCCUPATION IN NORTH KOREA: PUBLIC

OFFICER

YEAR OF ESCAPE FROM NORTH KOREA 2017

In North Korea, everyone watches everyone else— that’s how the system is set up. There’s even a saying that one in three people might be an informant for the MSS, and honestly, everyone knows it. My own father secretly worked as an MSS agent, spying on our neighbours for around 30 years, and I never had a clue. With surveillance so widespread, criticising the state or organising protests is completely impossible. Sure, there are demonstrations organised by the government, but they always push anti-USA and anti-South Korea propaganda. The idea of holding an anti-government protest is beyond imagination—it simply doesn’t exist.

NAME: L. M. R.

GENDER: FEMALE

YEAR OF BIRTH: 1980S

HOMETOWN: CHONGJIN

OCCUPATION IN NORTH KOREA: UNKNOWN

YEAR OF ESCAPE FROM NORTH KOREA: 2018

People who were watched included people like me— those who’d been to China, the very few who survived the Susong political prison camp, and anyone who had previously travelled to South Korea. There were informants we used to call “police spies. ”They weren’t actual police officers, but they secretly monitored people on orders from the police, and only reported if someone seemed suspicious. Every neighbourhood had at least one, and most people knew who they were. Then there were the MSS informants. These were just ordinary citizens who’d been given incentives—like tax breaks—in exchange for spying on certain individuals. Since Chongjin isn’t that close to the border with China, there weren’t many people like me who’d travelled there, so I ended up being under even heavier surveillance. MSS agents, police, the head of my People’s Unit, and even people at work were all keeping tabs on me. At my workplace, the secretary didn’t watch me directly but told others to keep an eye on me. The police mainly dealt with everyday crimes—things like theft or fights. But the MSS were the ones who tracked anyone who seemed politically suspicious. Watching people like me—that was their job.

NAME: K. H. S.

GENDER: FEMALE

YEAR OF BIRTH: 1970S

HOMETOWN: MUNDOK

OCCUPATION IN NORTH KOREA: RETAILER

YEAR OF ESCAPE FROM NORTH KOREA:2018

The guidelines said we had to monitor anyone who criticised the regime’s isolationist policies or called it a dictatorship. In North Korea, anyone could be a spy. I secretly monitored my own family, friends, and neighbours— and if anyone had found out, it would’ve completely destroyed my life and relationships. There were also MSS informants who monitored people more openly. MSS agents gave instructions directly, often setting up covert meetings in specific locations. The assignments changed depending on the political calendar—like the birthdays of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il. Around those times, I had to closely observe people’s behaviour and report on anything unusual. In 2015, I received a detailed set of instructions outlining the scope of surveillance operations—and my own husband was on the list. The guidelines said we had to monitor anyone who criticised the regime’s isolationist policies or called it a dictatorship. That really unsettled me. From that point on, I started to truly hate what I was doing.

NAME: C. S. Y.

GENDER: FEMALE

YEAR OF BIRTH: 1970S

HOMETOWN: HYESAN

OCCUPATION IN NORTH KOREA: UNKNOWN

YEAR OF ESCAPE FROM NORTH KOREA: 2019

You can’t trust anyone, no matter where you are. In North Korea, you’re always being watched—by your People’s Unit leader, by informants, by people you’d never even suspect. The surveillance system is everywhere. Some of it’s out in the open, and some of it’s completely hidden, especially the stuff run by the MSS. They plant spies among ordinary people, so you never really know who’s watching you. That’s why you have to be so careful with what you say. One wrong word, and you’re in trouble. You can’t trust anyone, no matter where you are. Even if you wanted to organise a protest, you’d need others—but how could you possibly work with people when you don’t know who’s reporting back to the authorities? No one even dares to think about it. Spies are everywhere—in your workplace, in your People’s Unit, just all around you. Even with your own spouse, you have to watch what you say, especially anything about the government. Sure, you share blood with your siblings. But a spouse? If they turn on you, they’re no different from a stranger.

NAME: Y. Y. Y.

GENDER: MALE

YEAR OF BIRTH: 1970S

HOMETOWN: HYESAN

OCCUPATION IN NORTH KOREA: ARTIST

WORKING FOR THE PROPAGANDA AND

AGITATION DEPARTMENT

YEAR OF ESCAPE FROM NORTH KOREA: 2017

Surveillance in North Korea is incredibly thorough. The authorities don’t just rely on official security agents or police officers—they also use something called the “core. ” In North Korea, people refer to them as “cores, ”but really, they’re just spies. There are even houses in each People’s Unit where these “core” informants operate. It’s through these channels that they collect information, and most People’s Unit leaders use these sources to get regular reports.

Mobile Phones

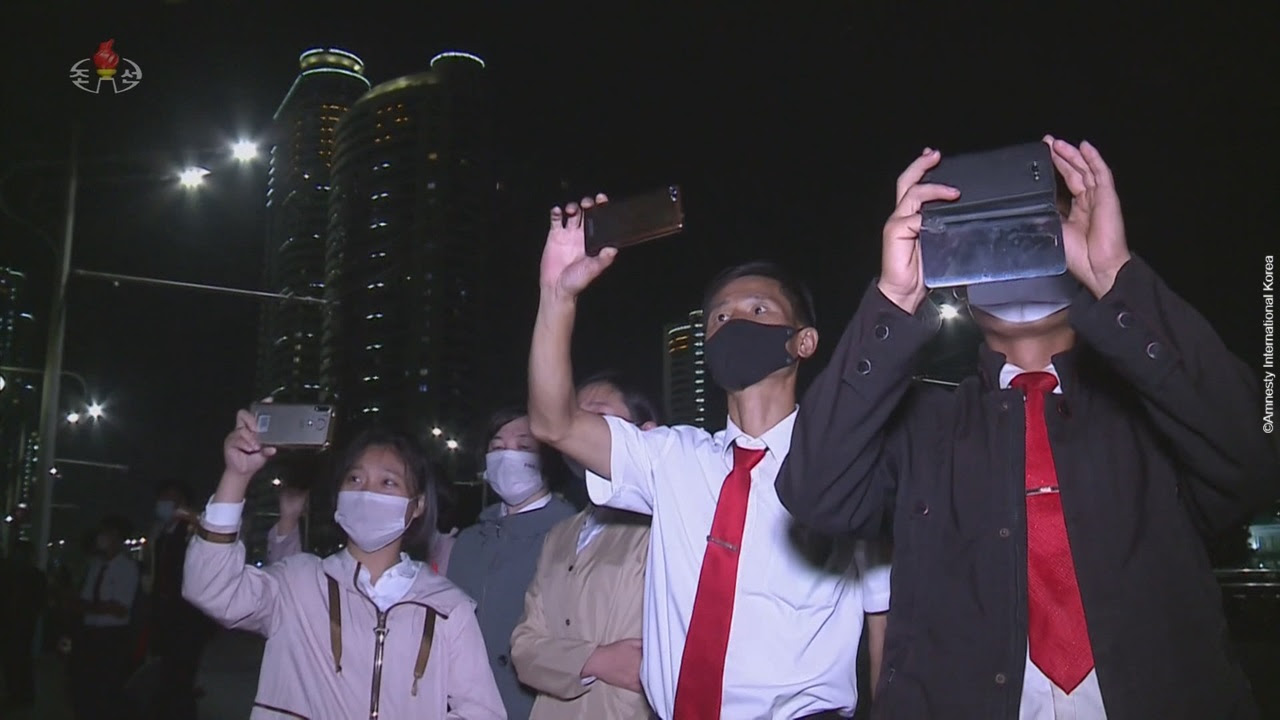

The number of mobile phone users in North Korea has grown significantly since the 2000s. According to Amnesty International’s 2016 report, it was estimated that the number of mobile phone subscribers exceeded 3 million at the time. With North Korea’s population around 25 million, this accounted for approximately 12%.

Some studies from the early 2020s estimated that, by the late 2010s, the number of mobile phone subscribers in North Korea had exceeded 6 million—a nearly twofold increase in just five years. This suggests that approximately one-quarter of North Koreans owned a mobile phone. The growing number of users underscores how mobile phones have become an integral part of daily life in North Korea.

However, the widespread use of mobile phones does not translate to greater freedom of information. Unlike most countries where mobile phones provide internet access and enable international calls, North Korea strictly prohibits both. Ordinary citizens are barred from accessing the internet, and only a small elite—state security personnel, some university researchers, and top officials—have limited, heavily monitored internet access. Foreign diplomats and media in North Korea face similar restrictions.

As of 2024, 99.9% of North Koreans remain completely unaware of what the internet is. Additionally, international calls are forbidden, making it nearly impossible for residents to contact family members abroad. This is especially significant given the hundreds of thousands of North Koreans who have defected to China or South Korea. Those who attempt illegal communication methods risk severe punishment. Even North Korean laborers sent abroad by the state are unable to maintain contact with their families, living in isolation under strict surveillance.

In contrast to the global norm of unrestricted internet access and international communication, North Korea’s continued ban on both underscores the regime’s oppressive control. In an era where information exchange transcends borders in real time, North Korea remains isolated, and its people are denied the fundamental right to access information.

Given these restrictions, what are mobile phones used for in North Korea? How do residents manage to communicate with the outside world? Below are testimonies from individuals who have fled North Korea, providing insight into the reality of mobile phone usage and access to information.

Name: Choi In-sun (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1990s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Rason Special City, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Translator

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

In North Korea, making phone calls to South Korea is impossible. People use smuggled Chinese mobile phones in cities near the border where Chinese communication networks can be accessed. To use these phones, you have to climb mountains for hours or move to border areas. These days, phone lines are often tapped, so you must be extremely careful.

Name: Lee Jin-ok (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1970s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Samjiyon City, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Former Switchboard Operator

Year of Escape From North Korea: 2017

In 2017, before I left North Korea, I would estimate that about 10% of the population owned mobile phones. Unlike South Korea, where you can freely access global information through the internet, mobile phones in North Korea are nothing more than symbols of wealth. They have no internet access, and the applications are limited to basic health-related content or North Korea-specific materials. People buy phones just to show off their status. You could see the envy in people’s eyes when someone carried a phone on a bus or walked around with it.

All mobile phones in North Korea are wiretapped. When a call is being monitored, the voice of the person you’re talking to starts to echo. That’s how you know you’re being eavesdropped on. It happens at least once every couple of days. At that point, you stop talking and only say what is absolutely necessary. While the Ministry of State Security cannot identify every single mobile phone owner in real time, they can trace the phone number and the location of the call.

Name: Jang Gil-soo (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 2000s

Gender: Male

Hometown: Sinpo City, South Hamgyong Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Student

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

I didn’t use a mobile phone, but even back then, most adults in North Korea owned one. In Hyesan, a border city, I’d say around 70 to 80 out of every 100 adults had mobile phones. Students like me were not allowed to have them. The phones were all smartphones, but they had no internet access. You could watch movies or take photos, but there was no way to search for information.

I heard there was something like an intranet in North Korea, but it’s strictly for domestic use. You can only access North Korean information. People use their phones to make calls, play games, and take pictures, but that’s it. They can’t connect to the outside world.

Name: Gang Na-hyun (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1970s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Tanchon City, South Hamgyong Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Librarian

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

Every household in North Korea has a mobile phone, without exception. This is because people need them for business purposes. Whether it’s something as simple as selling vegetables, all North Koreans make their living through business activities. Well-off families typically have a mobile phone for each member, while less affluent households manage with at least one. Even in rural areas, mobile phones are common. Young people are particularly eager to own one, as not having one feels like a loss of dignity. However, there is no access to the internet at all.

Name: Kim Han-il (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1990s

Gender: Male

Hometown: Wonsan City, Kangwon Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Merchant

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

These days, all mobile phones in North Korea are smartphones, and as far as I know, they are all made in China. If you open up a device, you’ll find that it’s composed entirely of Chinese components. During my time in North Korea, I frequently repaired mobile phones. People often steal or find lost phones, and since the level of communication technology is not very advanced, it’s impossible to track down the original owner. So, people have the phones repaired or the CPUs replaced and continue using them. From what I know, the phones are primarily imported from China, assembled in North Korea, modified with a North Korean operating system, and then sold.

All internet access is blocked, and there is no Wi-Fi. Mobile phones distributed within North Korea have internet access blocked at the system level, making it impossible for individuals to bypass this restriction. Even if someone managed to access the internet using advanced technology or a different system, the country’s radio detection systems would catch them and prevent access.

Name: Kim Hye-soo (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1970s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Yonsa County, North Hamgyong Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Secret Informant

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

To make a call from North Korea to South Korea, you must use a Chinese phone. In North Korea, there’s something called a “kiss call.” This method involves placing a Chinese phone, which is in the middle of a call with someone in South Korea, face-to-face with another phone that is connected to someone in a different region of North Korea. This allows for indirect communication. For example, by paying extra, a person in South Pyongan Province can avoid traveling to the border and instead make the call from their current location. The two phones are held together to complete the call. However, this method is heavily wiretapped, and the sound quality is poor.

Mobile phone calls are often wiretapped, while landline calls are less likely to be monitored. If you try to make a kiss call to South Pyongan Province, it will inevitably be intercepted. The chances of being caught are lower when calling from the border region, but even there, making a call from inside your home will still be monitored. That’s why people go to the mountains or the river near the border to make calls. However, due to increased control along the North Korea-China border, making calls has become much more difficult. Since the government issued strict orders to crack down on those violating COVID-19 quarantine measures, surveillance has intensified significantly.

It’s hard to hear the other person clearly during a kiss call. After I came to South Korea, I contacted my younger sister, who lives in South Pyongan Province. I wasn’t calling to send her money but to let her know I was alive. This was in early 2020. I had been in contact with her until the calls stopped at some point. My sister must have been worried, but you can’t make a call for free. I had to send money to my family in North Korea, and brokers take a percentage of the amount sent. Without that, they won’t assist you, even if all you want is a simple phone call.

I made calls to my sister in the same way—by sending money. I sent 1 million South Korean won (700 US dollars), along with an additional 200,000 won, and asked the broker to meet her in person to connect the call. The broker, who was from Musan, arranged a kiss call from Mundok in South Pyongan Province, and I recognized my sister’s voice. The women in my family have a similar tone to mine, making it easy to identify. Some brokers try to deceive you just to take your money, but you can tell by the voice. There was a lot of noise during the call, but I recognized her voice immediately. It is still possible to make phone calls by sending money. However, since 2020, it has become much harder to do so. While I was able to contact her in early 2020, starting in 2021, it became significantly more difficult, likely due to stricter controls.

To use a Chinese phone, you need to be connected to a Chinese broker who can top up the phone’s balance. Simply owning a Chinese phone isn’t enough—you need to pay for the Chinese communication network, which North Koreans cannot do themselves. As a result, they must rely on a broker in China. This means that only those with connections to a Chinese broker or partner can act as brokers.

Name: Jang Jin-kyung (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1990s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Hoeryong City, North Hamgyong Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Unemployed

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

The mobile phones I used in North Korea were similar to those in South Korea, with apps and other features. If you wanted to install a game application on your phone, you had to visit a computer expert and purchase it. These individuals were professionals working independently. I believe South Korean apps could also be installed on North Korean phones, but who would risk their life to do that? Most people would refuse, thinking it’s not worth the danger for something so trivial.

North Korean phones can do almost everything South Korean phones can, except access the internet. The physical devices are the same, but internet access is blocked—that’s the main difference. There’s no way to make an external connection. The smartphones used in North Korea are not made locally; they are imported from other countries. They look the same as the ones we use now, but their systems are modified to block any connection to the outside world. As a result, the exterior and even the app designs are similar.

Landline phones had already been wiretapped for years before I left North Korea. I heard that mobile phones became wiretappable starting in 2018. My guess is that by now, wiretapping is fully operational, even for private mobile phones.

People generally use their phones for sending texts and making calls. North Korea is different from South Korea. In South Korea, even though Seoul and Busan are far apart, cars travel freely between them. In North Korea, however, people must rely on phones for communication because traveling long distances is not as easy. This is the main reason phones are needed—to communicate over long distances.

In South Korea, communication fees are paid after use, but this system doesn’t exist in North Korea. All phones are prepaid. You can top up your phone only at designated stores, which are connected to the state office that manages phones. At these stores, you pay money, and the balance is added to your phone. The vendors are civilians who buy phones from the state at a low price and resell them to people like us for a small profit.

Name: Jung Hwa (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 2000s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: High School Graduate

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

These days, making international phone calls has become impossible—you now receive a video instead. The last time I made contact was this January, and I received a video instead of a call. In 2021, when I sent money to my family in North Korea, I could sometimes make video calls and send messages through WeChat (Weixin), but that’s no longer possible.

Since mobile phones are available in North Korea, the broker would record a video of my relatives, where they would talk about how much money they received or how they were doing. The broker would then transfer the video to another phone and send it to me. That way, I could see my parents’ faces. I heard that due to heavy surveillance, a broker cannot visit the same house twice. So, the broker would visit our house, deliver the money, record the video, and leave immediately. Once I received the video, I would send the broker their payment.

In Hyesan, which is close to China, Chinese signals, or “antennas” as they call them, can be picked up. If you turn on a Chinese phone in Hyesan, you can get a signal. It doesn’t work with North Korean phones, but with Chinese phones, you can get a signal and even make international calls.

There’s no Wi-Fi. The internet doesn’t exist at all. However, I’ve heard that in places like Pyongyang, there are ways to connect to Wi-Fi. I was told this is why North Korean players appeared in the statistics for a global game. A person I came to South Korea with said their parents held high-ranking positions in the Party. According to this person, the children of Party officials can access the internet. I’m not exactly sure how it works, but I’ve heard that the children of high-ranking officials in Pyongyang have internet access.

The Inflow of information

North Korean residents live in an environment without free access to outside information. Accessing outside information within the country is strictly regulated by the authorities.

While internet access is readily available worldwide with any connected device, it is restricted to a very small group of elites in North Korea, who themselves are subject to strict surveillance. International travel for ordinary people is impossible, and leaving the country is only permitted for state-beneficial purposes. North Koreans are also cut off from international calls, with equipment installed at the borders to block such calls. Telephone calls in border regions are often wiretapped by the authorities.

North Korean residents have routine access to extremely limited outside information. The regime only disseminates information which has undergone strict censorship, leaving North Koreans dependent on the state’s-controlled narrative.

Since the 2000s, various international human rights organizations and individuals have attempted to improve North Koreans’ access to information. Shortwave radio broadcasts have been one of the primary non-physical means of information dissemination. Physical methods have included CDs, DVDs, USBs, and SD cards. Additionally, the release of plastic bottles along the rivers in border areas and the use of balloon campaigns, commonly known as “ppiras (propaganda flyers and leaflets)”, have been employed for the last decades. North Koreans have had access to outside information through these channels, however limited.

However, since the border shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the flow of information has faced significant challenges. Information dissemination via USBs and SD cards, which had been one of primary such methods over the past decade, has been severely affected by tightened security along the North Korea-China border. Amid these challenges, some South Korean civil society groups have announced that they will continue to send flyers to North Korea. They argue that in the current situation, flyers can still help bring outside information to North Koreans and that such actions constitute an exercise of free speech.

Most North Korean escapees who were interviewed by AIK spoke highly of the importance of introducing outside information into North Korea in terms of raising human rights awareness and improving access to information for North Koreans. They also emphasized the ongoing need for information dissemination. However, unlike the distribution of information via USBs or SD cards, there was a generally negative reaction regarding the effectiveness of balloon campaigns in border areas. They shared the common view that flyers rarely reach North Korean residents, have limited capacity to convey information compared to other media outlets, and that people are often more interested in the physical goods attached to the flyers rather than the messages they contain. In conclusion, it seems that while North Korean escapees broadly agree on the importance of bringing information into North Korea for the promotion of human rights, they believe that careful consideration must be given to the methods and forms of delivery.

Below is a summary of the recent North Korean escapees’ views on the inflow of information into North Korea and the effectiveness of balloon campaigns. As people who came from North Korea, they spoke candidly about their views on balloon campaigns and information dissemination into North Korea. Their testimonies offer insights into what methods and directions for information delivery might be most effective in improving North Koreans’ access to information.

• Name: Jang Jin-kyong (pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1990s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Hoeryong City, North Hamgyong

Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Unemployed

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

I don’t think the balloon campaigns are effective at all. They only fly as far as the mountain areas around Kaesong, but no further. That area is already a restricted zone, completely sealed off, so when flyers or leaflets land, they are immediately burned. I’ve heard that a few people picked them up while foraging for wild vegetables in the mountains. But I don’t think it has much of an impact, given the severe punishments imposed. The content on the leaflets wouldn’t suddenly transform a person’s perspective. I heard that rice and other things are also attached. If I’d seen one, I would’ve just taken the rice and left the rest. Taking the leaflets would’ve been risky —it would get me into serious trouble, so why bother?

• Name: Hwang Su-ra (pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1990s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Chongjin City, North Hamgyong

Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Graduate Student

• Year of Escape From North Korea: 2019

I wouldn’t say that the balloon campaigns are 100% helpful, but they are effective to some extent. What’s important is the method of delivery and the content of the materials. Well… I do think it’s important. The influx of information is necessary, as access to it is so limited in North Korea anyway.

I think using USBs is the best method. Flyers don’t travel that far to begin with. The area 2 km within the demarcation line is all part of the demilitarized zone, so even if they fly across, only a limited number of residents can see them, and the authorities will confiscate them all. So, there isn’t much point. In North Korea, SD cards are preferred over USBs because they are easier to carry. I also agree. This method seems better for the influx of information. Even if you send flyers or rice, the people who receive them won’t eat the rice, and the authorities will just take everything away. It’s too unrealistic. While I see the value in flyers for enhancing access to information, I think the idea itself is too outdated. They won’t reach the population. Where do you think these will go? They won’t even reach Pyongyang and will just fall near the border, where the population is sparse— practically non-existent. It’s all rural, with only one or two houses every few kilometers. Moreover, many of the people in rural areas are not very educated. To change people’s views, information needs to reach educated populations in densely populated areas, where they will feel disenchanted and start rising up in protest. So, to me, sending flyers seems odd.

• Name: Choi Sun-yong (pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1970s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang

Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Smuggler

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

I don’t believe that flyers really inform people of anything. I think they are somewhat dangerous. The information doesn’t reach the ordinary people, and instead, it works against North Korean escapees. The authorities are aware of the flyers because when they are discovered, they are burnt. Yet it just creates a more negative perception against those who left. The government tightens its control over escape routes, making it even harder for people to escape. Most people I know who left North Korea generally have a negative opinion of sending flyers, as the routes keep getting blocked.

• Name: Ko Kyong-rae (pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1980s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Manpo City, Chagang Province,

North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Unknown

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

I don’t think the balloon campaigns are effective. The balloons and their contents don’t reach the people—they just don’t. Even if they somehow made it all the way to Hyesan (300~400 km far away from the DMZ), if someone picks one up, they will get caught. People don’t touch them; they just report it to the law authorities. In the end, the flyers end up with the Ministry of State Security. If someone like myself picked one up, it would only be a matter of time before it was discovered. In North Korea, people say that two or three out of every five are spies. That’s why I said it’s only a matter of time before others around you find out. No one wants all three generations of their family to be arrested just because they picked up something from South Korea. I just leave it because that one flyer isn’t going to change my fate or turn the whole society upside down. In short, they’re unnecessary.

I had a chance to see those people involved in the campaign sending flyers with Kim Jong-un’s face on them. Those actions only provoke North Korea. Of course, it’s my own opinion. However, North Korean escapees during the Kim Il- sung and Kim Jong-il eras might be doing that because they are not aware of the current situation in North Korea. It’s not going to change anything. An ordinary person would never pick them up because that’s a sure way for their family —not just the immediate members, but the entire clan—to end. The family of anyone who picked up a flyer would be taken away without a trace. Even if someone did pick them up, it would only be to report them to the Ministry of State Security. That’s why I don’t believe those flyers will change people’s minds.

If one really wants to have some impact, they should send things like USBs through China to penetrate the culture— like sending dramas or movies. People would secretly share and watch them among close friends. But honestly, sending flyers like that only provokes the North Korean regime more, whether it’s Kim Jong-un or Kim Yo-jong. And what would be the consequences? Hostility is bred against North Korean escapees. More pressure and harm are done to the families we left behind. What frustrates me about those who send these flyers is that, while I’m safe being here, the families left behind live under tight surveillance because of us. Many people are watching my family closely. In such a situation, if one flyer flies over, there will be public gatherings saying, “Escapees are traitors.”

Imagine how painful and anxious that would make our parents and siblings feel. This is completely unnecessary. I believe that not only for the people here in South Korea but also for those who are still in North Korea, such actions should not be taken. Remember when Kim Yo-jong was angry and blew up the building? That wasn’t the end of it; I heard that the restrictions against the families of North Korean escapees were severe. So, how much hatred do you think people in North Korea feel toward those who escaped and came to the South? Wouldn’t they think, “You left for your own sake, but now you’re causing us suffering”? Yet, these people believe that sending flyers will act as a stimulus for North Koreans to change their minds, but that’s absolutely not true. It won’t change a thing. Under Kim Jong-un, the situation is tighter than ever.

A banner and leaflets condemning North Korean leader Kim Jong Un are tied at a balloon as North Korean defectors prepare to release it during a rally marking the 6th anniversary of the sinking of South Korean naval ship “Cheonan” near the border with North Korea in Paju, South Korea, Saturday, March 26, 2016. An explosion ripped apart the 1,200-ton warship, killing 46 South Korean sailors near the maritime border with North Korea in 2010. The sign read “Spirits of Cheonan ship want Kim Jong Un’s head to be cut off.”(AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

• Name: Lee Sang-sil (pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1960s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang

Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Seamstress

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

I wish the activists who are from North Korea but are now in the South would stop sending flyers to the North. The reason is that after such actions, there were public gatherings in North Korea where they said things like, “Eliminate the escapee scums.” The families of those who left North Korea have suffered greatly as a result. The Ministry of State Security called in those family members and interrogated them, asking if they had colluded with South Korea to send their families over. I have an older brother in North Korea. He faced severe discipline. That’s why we, as North Koreans living in South Korea, have confronted those people who send flyers or engage in YouTube activities. We have pleaded with them to stop. Those who managed to settle in South Korea live without worry, but why do they have to bring suffering to our families in North Korea, who are already struggling to survive? We have often sent messages to those people, asking them to stop. Those who send balloons argue that the flyers allow North Koreans to access outside information and awaken their minds, but that’s not true. The North Korean authorities block everything. Instead of doing such things publicly, they should aim to tell the world the realities of North Korea to the world. The regime effectively shuts down information, so even if flyers are sent, they won’t reach the people. On the contrary, they only harm the people further. It’s not just me. Most of us who left North Korea share the same opinion: stop sending things to North Korea, but inform the world about the realities of North Korea. The world should know about North Korea’s truth. North Korea is isolated due to UN sanctions, and that’s a good thing. The president of South Korea should not meet with Kim Jong-un, and neither should the U.S. president. North Korea should be completely isolated from the world. That’s what we, who left North Korea, believe needs to be done. We need to tell the world about the human rights situations we experienced in North Korea. I would tell people that I should have held a press conference when I first arrived in South Korea. Well, that’s how I felt at least. My husband is currently in a political prison camp.

• Name: Kim Eui-du (pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1970s

• Gender: Male

• Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang

Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Law Enforcement Officer

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

When flyers are sent, people are made aware of the truth, which encourages them to leave North Korea and creates a fantasy about South Korea. But no more. However, for the leaders at the top, the balloon campaign can only be perceived as an ideological offensive, as it seems to reflect South Korea’s duplicity: talking about unification on the one hand while sending flyers on the other. This just makes them more resentful. For example, if positive images of South Korea, the free world, or capitalism are conveyed only to the people, the result will just be defections. The people are unlikely to think, “We’ve been deceived all this time; we must protest.” Instead, it would likely further divide North and South Korea, entrenching the wall separating them.

• Name: Kim Hak-woo (pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1990s

• Gender: Male

• Hometown: Kimjongsuk County, Ryanggang

Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Former Soldier

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

I think the balloon campaign has some effect. Sometimes, when the winds are favorable, the balloons reach all the way to Hwanghae Province. The vinyl material is so good that people collect it to cover their crops. I’ve heard the quality is excellent. As for the items that are dropped, there’s no food, but there are one-dollar bills. There are a lot of one-dollar bills in North Korea, and I think most of them probably come from these balloons. I believe there are more one-dollar bills in North Korea that come from those balloons than from abroad. A dollar can get the boys in the army a kilogram of bread, so that’s quite helpful. While the money would be spent, I think people would still pick up the flyers.

• Name: Seo Wang-il (pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1990s

• Gender: Male

• Hometown: Pochon County, Ryanggang

Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Train Driver Assistant

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

Sending balloons to North Korea is obviously effective. To be frank, I didn’t know that South Korea was such a rich country. I also didn’t know that South Korea accepted us. North Korea needs to wake up from within since that can’t be achieved by gunshots from the outside. I believe the fastest route is to send information to North Korea. That effort is very necessary.

However, I am not sure about things like sending USBs. The purpose is to inform the North Korean population, but their lives are put in danger if they are caught viewing the contents. Still, I think flyers or radio programs are fine.

In the region where I lived, I couldn’t listen to South Korean radio. But in provinces like Kangwon Province, Hwanghae Province, and Kaesong City, you can pick up the signals. I know a guy from Kangwon who has been interested in electrical stuff since he was a kid. He told me he listened to lots of South Korean radio, which made him think that he should move to South Korea.

Reactionary Ideology and Culture Rejection Act

In December 2020, the Reactionary Ideology and Culture Rejection Act was passed in North Korea. The Act, which was revised to be more punitive in August 2022, was confirmed to be a serious infringement of the freedom of expression of North Korean residents, raising significant concerns within the international community.

According to the North Korean authorities, the purpose of this law is to stop “the inflow and distribution of reactionary ideology and culture and anti-socialist ideology and culture” and to “strengthen the sense of ideology, revolution, and social class.” In other words, Reactionary Ideology and Culture Rejection Act is a law aimed at blocking the inflow of external cultures and suppressing the further spread of any introduced foreign cultures. To this end, the law stipulates severe punishments for violators.

This law stipulates that individuals who view or possess external materials classified as impure propaganda, such as books, photos, drawings, movies, recordings, and edited materials from hostile countries and puppet states (South Korea), can be sentenced up to over 10 years of reform through labor. Those who distribute or encourage group viewing of these materials can face the death penalty. For example, a person who acquires a data storage device, such as a SD card, containing South Korean movies or TV shows and shares it with acquaintances could potentially be sentenced to death.

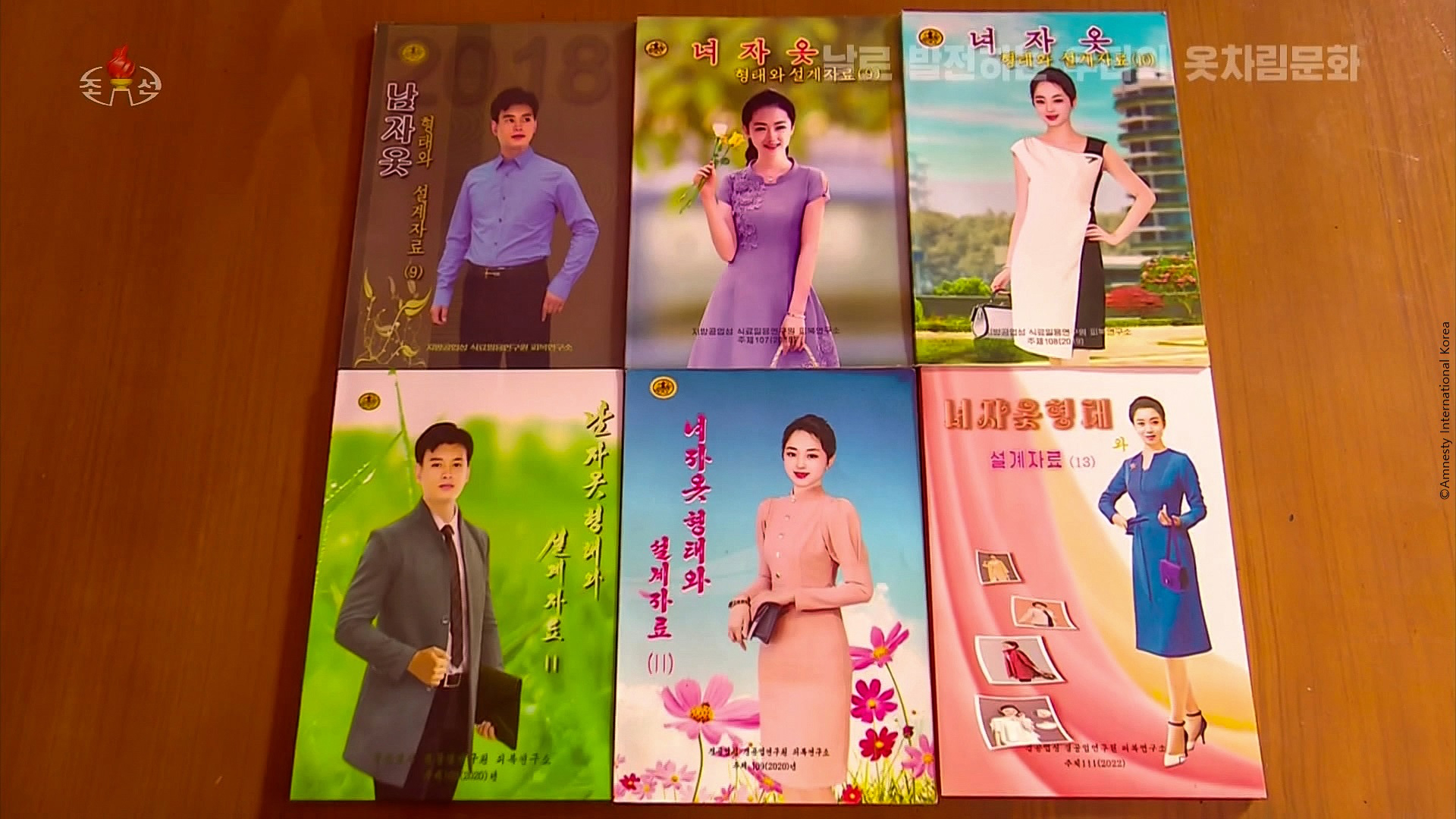

Another notable point is that individuals who introduce or distribute “exotic” cultures, including foreign clothing, are sentenced to disciplinary labor. In short, the law regulates residents based on their looks.

Since the 2000s, North Korean residents have come across foreign movies and dramas, including those from South Korea, through imported USBs or SD cards. Becoming increasingly more curious about the new fashions and styles they see in these videos, they have started to imitate them. This includes not only importing clothes and shoes of the latest fashion from places like China or making them themselves but also copying hair and make-up styles. This behavior directly contradicts the “socialist” lifestyle the authorities have emphasized.

To control this, the authorities have mobilized organizations like the Ministry of People’s Security and inspection units to continuously regulate so-called “anti-socialist” behaviors. This is not a new phenomenon. In the past, such individuals were given administrative guidance, like warnings or relatively mild sanctions. Now, however, under the Reactionary Ideology and Culture Rejection Act, they are subjected to harsher punishments, such as disciplinary labor. The level of punishment has become significantly more severe.

The introduction of the Reactionary Ideology and Culture Rejection Act clearly indicates the authorities’ intent: to root out the raid-spreading anti-socialist culture. Such a strict response reflects the fact that the authorities are extremely concerned about the increasing introduction of foreign cultures and the spread of “anti-socialism,” and regard them as serious threats.

However, exerting control over the foreign culture that has spread in North Korean society seems nearly impossible. Despite the regulations, many North Korean residents imitate fashion from South Korean media, covertly and sometimes even openly, and this has become an unstoppable phenomenon. On the contrary, it is reported that they harbor a deep grudge against the authorities’ attempts to regulate and control them.

The following are excerpts from testimonies of North Koreans who recently left the country, on the topic of the regulation of personal appearance in their daily lives. Although all testimonies reflect the period before the introduction of the Reactionary Ideology and Culture Rejection Act, they still confirm the severe control over appearance and clothing enforced by the North Korean authorities. By looking into the lives of North Koreans, who even have their appearance controlled without any respect for their individual expression, we can infer the dire state of freedom of expression within North Korea.

• Name: Kang Chol-ho(pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1990s

• Gender: Male

• Hometown: Pochon County, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Farmer

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

The Youth League does a number of activities, one of which is the “Inspection Unit.” One of the roles of the Inspection Unit is to regulate indecent behavior. In North Korea, you can’t dress as you wish. Particularly, there are many peculiar clothes from China. People wearing such clothes are considered ideologically impure, and the Inspection Unit regulates them. The Inspection Unit typically operates in small groups, wearing identifiable badges. Generally, young people dress uniquely to stand out more than older people. The unit targets these individuals. Some of those caught resist. These people are taken away for “culture education,” where they are made to study. They are not beaten or anything like that. At one point, bell-bottom pants were in fashion in North Korea. They weren’t allowed since the party had banned them. However, there still were people who wore them. I remember there being strict regulations on those people.

• Name: Baek Sang-chol(pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1980s

• Gender: Male

• Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Smuggler

• Year of Escape From North Korea: 2018

I remember, like twenty years ago, there were no South Korean movies, so I had no idea of such things. I would simply go to theaters to watch North Korean movies like Im Kkeokjeong. But people went to theaters to fight rather than to watch a movie. It was common to have a fight then.

But nowadays, rather than going to theaters, young people stay at home and watch South Korean dramas or adult movies with close friends. And going somewhere and doing drugs is a trend now. I noticed that kids these days use South Korean words when they talk or make jokes. It’s not that they think differently about the system compared to our generation; I think they regard the culture as inferior to that of South Korea. They would think, “Wow, that’s trendy,” or “Oh, that’s the popular hairstyle,” when they see South Korean fashion or hairstyles from dramas and celebrities.

In North Korea, everyone has to have neat hair. But kids nowadays grow their side hair and don’t trim the back. These are all subject to regulation by inspection units from the Youth League, the university students, and the Women’s League. Some women who are told to stand right where they were caught and are not allowed to leave end up crying. For men, they are sometimes ignored because it could lead to a physical fight.

• Name: Lee Hwa-jong(pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1980s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: College Student

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

In North Korea, women are only allowed to wear trousers with plaits; jeans are completely prohibited, and leggings are not allowed either. Something like slacks is okay, but they must have plaits and must not be tight. Additionally, you might get your mobile phone checked on the streets at any time. The Youth League is responsible for such regulations.

There is a group called the Inspection Unit of the Youth League, and they are in charge of enforcing these regulations. I was an inspector once when I was in university. I had to check on people’s clothing, even though I wanted to dress in the same style. If you are caught, you are dragged to the League building. There, they will simply rip the fabric at the knee part with scissors so that you can’t repair it and wear it again. If you have your hair dyed, your hair will be cut as well. I dyed my hair once, so when I went out in winter, I would pull down the hood of my long padded coat whenever I saw a sign of inspectors. I hated all that. They would just rip apart perfectly fine and even expensive trousers. It’s not like they would get you a new pair.

Nevertheless, you won’t be sent to detention facilities like a disciplinary labor camp for your clothing. It’s more of a formal regulation because it was ordered by Kim Jong-un. Unless you are caught watching South Korean dramas or something similar, you won’t be directly punished.

• Name: Lee Su-son(pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1960s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Seamstress

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

Jeans were regulated even when I was in North Korea. I was an inspector in the Women’s Union and used to regulate jeans. In North Korea, short skirts that are about 5 cm above the knee are allowed, but those that are 10 cm above the knee, tight-fitting or sleek trousers, and jeans are subject to regulation. Jeans are regarded as a symbol of capitalism. People can’t think about wearing them. In fact, jeans don’t exist there. During the Arduous March (mid to late 1990s), there was a time when jeans were introduced from China. I wore jeans for a while and they were so comfortable and good. We wore jeans then. But not long after, the government banned them. Jeans were labeled “American trousers”. At the same time, another form of tight trousers called “mombbe” was labeled “Japanese trousers” and were regulated intensely. Clothes that were considered South Korean, regardless of type, were heavily regulated without question.

• Name: Yang Yong-hee(pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1990s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Soldier

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

These days, even teenagers and those in their 20s can’t dress as comfortably as they like. If you don’t wear Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il badges, you will be stopped. If you wear sleek trousers (those made of fabric that fit closely to the body), you get stopped. You can’t grow your hair long either; there are regulations. You can’t grow it however you want. In short, you can’t do anything the way you want. If you deviate from the rules, you get stopped. If you get caught, you have to pay a fine or something similar. I got caught a lot when I was a student. I got called by the Youth League and had to give them things like a few cans of enamel or some mops. Whether you’re a worker or a student, if you’re young, the Youth League will stop you. The inspection units include not only those of the Youth League but also the university student inspection units and those of the Women’s Union. The Women’s Union inspectors are mothers who go around regulating women. The university student inspectors target university students.

• Name: Kim Hee-sook(pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1970s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Mundok County, South Pyongan Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Local Retailer

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

In South Korea, the police do a lot of different things, but in North Korea, if you ask me what the police officers focus on the most, I would say they are mainly obsessed with taking money by regulating people wearing sunglasses, black leather jackets, or tight trousers.

Once, I was riding my bike wearing sunglasses because the sun was blazing in the summer. I was riding energetically when suddenly I heard a sharp sound of a whistle. I thought, “Oh no, I’ve been caught!” and stopped. It turned out to be a police officer I knew. I asked, “Why am I being stopped?” He replied, “Comrade, look at how you’re dressed in these times! You’ve got some nerves to go around like that.” I replied, “I had an eye issue recently, and the doctor told me to wear sunglasses.” He laughed at me. The accent in the northern regions (Hamgyong and Ryanggang Province) is different from mine. I speak with a South Pyongan accent and have a unique voice, so he let it slide because I’m a woman and he’s a man. I used to be the head of the People’s Unit, so I had connections with local police officers. Then, he told me to stay there for a bit, then said, “Next time, don’t wear such black-covered things,” and let me go. This is how they usually regulate such things.

Nobody wears jeans in North Korea. Trousers must be like Kim Jong-un’s wide-legged trousers. When I saw Kim Jong-un standing next to President Moon Jae-in, I immediately noticed, “Why is President Moon wearing tight trousers?” North Koreans prefer wide-legged trousers like Kim Jong-un. If you wear tight trousers like President Moon, you’ll definitely get caught and fined.

Besides the police officers, inspection units regulate clothing. Many organizations have their own inspection units, including those of the Youth League, Women’s League, and university students.

• Name: Ju Yang-ok(pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 1980s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Self-employed

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

The old generation is completely steeped in Juche ideology (North Korea’s official ideology, which theoretically justifies the one-man rule under the Great Leader, Kim Il-sung). However, people in their 20s to 40s follow South Korean hairstyles and fashion, even though no one talks about it openly. People now think when they see a well-mannered person, “Wow, he must have watched a lot of South Korean movies and dramas,” or “This person must have seen a lot of foreign stuff.” There is a huge gap between these people and ordinary folks. You can tell just by how they behave at a meeting or an event, or by how they utter a word. However, you have to be like us, who watch South Korean dramas, to be able to notice that.

Clothing is still regulated in North Korea. Inspectors literally go around with scissors, cutting not only clothes but also hair. This is a downright insult to one’s dignity. University student inspectors go around cutting people’s hair. Additionally, women from the Women’s Union regulate those who dress weirdly. Young people protest against such regulations and try to keep their South Korean style. I must say, that style is really neat and good-looking. So, young people argue with the inspectors, saying, “Don’t come after us, go after those people wearing torn clothes!” Here in South Korea, torn clothes are a fashion trend, but in North Korea, many people wear torn clothes because they are too poor. The young people are referring to those people.

• Name: Jang Yong-ji(pseudonym)

• Year of Birth: 2000s

• Gender: Female

• Hometown: Chongjin City, North Hamgyong Province, North Korea

• Occupation in North Korea: Unemployed

• Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

Young people watch South Korean dramas a lot. They often imitate the hairstyles and clothing they see in these shows. In North Korea, men aren’t allowed to grow their hair long. Stereotypes are very strong: men must keep their hair short and women must wear skirts. Women can’t grow their hair below the shoulder or get perms either. Even in 2019, when I left North Korea, inspections were conducted every 10 meters on the streets. The Youth League inspection units carried out those inspections.

When you get caught, you have to work at places like construction sites. You are sent to Storm Troops and forced to work for 15 days to a month. Your family is only informed after you have been sent. However, if you have money, you can buy your way out. There are specific times when regulations are strict. For instance, if there aren’t enough construction workers, the regulations become intense. If the workforce is sufficient, they just take money and let you go. They enforce the rules according to their needs. It doesn’t matter if you are a woman or a man. Even young people are sent if they are old enough to work. The elderly are exempt. Adults are regulated by the Women’s Union.

THE AGRICULTURAL SECTOR

Over the past few decades, North Korea’s agricultural sector has faced systematic difficulties owing to a number of factors. Key inhibiting factors to development include government policy failures, natural disasters, shortage of external supplies such as fertilizers, fuel, and agricultural equipment due to sanctions and COVID-19 prevention measures, outdated technology, and low labor morale among farm workers. As a result, North Korea’s agricultural productivity has been known to fall short of its potential production capacity. Given North Korea’s heavy reliance on domestic food production for its food supply, its low agricultural output has been regarded as a significant threat to national food security.

Recently, the authorities have prioritized the ‘Agriculture First Policy‘ as the foremost strategy to address chronic food shortages. They have pressed hard to enhance agricultural productivity through various initiatives, such as the introduction of new technologies and institutional reforms in the agricultural sector. Despite these efforts, overall conditions, ranging from social infrastructure to essential materials, remain inadequately developed. Consequently, these efforts have merely become slogans in name only. It has been shown that these measures have failed to noticeably enhance agricultural productivity, only exacerbating the confusion and hardships faced by agricultural workers (farm members).

All North Korean farms, regardless of their type, are practically owned by the State. Collective farms, which play a significant role in agricultural production in North Korea, are divided into regional units (typically “ri”). Collective farms serve as both communal farms and living communities, collectively managed by local farm members. Farm members are forced to follow in the footsteps of their fathers and grandfathers except under special circumstances. Without the State’s permission, they find it difficult to pursue other occupations or leave rural areas. Merely being born into a farmer’s family exposes individuals to a number of human rights violations, including restrictions on the freedom of occupation.

Farmers transplant rice seedlings in a field in Chongsan-ri, Kangso district, Nampho, North Korea, Sunday, May 12, 2019. (AP Photo/Cha Song Ho)/2019-05-12 16:37:16/

Despite the arduous labor, farm members are subject to extremely poor treatment. Due to harsh conditions, it is typical for the absolute quantity of the annual farm harvest to fall below target. Harvested crops are distributed to the farm members after the State’s quota (including military supply portions) is first taken away. However, due to low productivity that results in yearly harvests falling short of expectations, if farms fail to meet their allocated quotas, farm members inevitably end up with less portions than they are due.. In the end, the food made available to agricultural families is often far from sufficient to sustain basic living. To make matters worse, a considerable portion is often siphoned off by mid-level cadres during the distribution process. Consequently, it is not uncommon for farm members in rural areas to resort to practicing usury or stealing food during the spring lean season, leading to a structure whereby farm members find it difficult to break free from the recurring cycles of hunger and poverty each year. Considering the overall contraction of North Korea’s economy since COVID-19, it can be speculated that the recent situation faced by farm members has further deteriorated.

Name: Park Yang-hak(pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1960s

Gender: Male

Hometown: Hyesan City, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Farmer

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

You can witness the tragedy of North Korea through the reality of its farms. In North Korea, if you are male and your parents are members of a collective farm, both you and your children are destined to work as farmers for the rest of your lives. There is no room for choice in your occupation; it’s farming without question. Even if a farmer’s child completes their 10 years of military service, they must return to the farm. They cannot work in any other sector. They are made to work under the name of ‘rural camp enforcement’. Consequently, there are numerous cases where farmer-parents are resented by their children. The children are unhappy, questioning, ‘Why is it that when most other parents are laborers, my father, as a farmer, forces his children to work in a farm like this?’ It is a tragedy that farmers cannot choose the work they want to do.

Even if farmers’ children wish to enroll in university and pursue academic careers, they are often restricted by the State. While some manage to succeed in doing so, they represent only a tiny fraction, about one in every ten. To begin with, attending a university costs money, but farmers are the poorest people in North Korea. Unless the children have an exceptional level of knowledge, it is impossible for them to pursue higher education. Generally, children of regular laborers face fewer obstacles in university enrollment. However, the admission pool for children of farmers is limited. This situation highlights clear discrimination based on one’s songbun. There is a social perception against the farmers’ children, such as ‘Don’t think of anything else. Just stay at the farm.’ or ‘Educate yourself about rural camp enforcement.’ The State imposes restrictions on every aspect of farm members’ lives. In reality, a farmer’s child going to university means breaking through competition rates of thousands to one. Without the requisite knowledge and money, they are forfeited of an opportunity even if they wish to study.

Farmers represent the most unfortunate group in North Korea. I also had bitter resentment towards my parents. There is a saying in the North: ‘The fate of farmers is eternal.’ In other words, farmers, their children, and their grandchildren are all destined to be stuck with farming forever. Children of farmers cannot marry freely. A farmer’s daughter struggles to find a husband. If a farmer’s daughter marries a laborer’s son, the son’s family would face disadvantages. As the situation in rural areas worsens, so does the food situation. The state is desperate to maintain the number of farmers by supplementing additional farmers. One such potential source is a male laborer married into a farmer’s daughter, who would then be sent down to a farm

In North Korea, every institution receives an annual plan from the State. This includes farms. However, how could people carry out the plan without fertilizers, pesticides, and funds? Consequently, the collective farm mobilized its members, having them cut down all the trees in nearby mountains and selling the logs to China. This was how they managed to obtain the necessary materials for farming. In short, some members sold trees to China and used the money to get essential materials such as fertilizers, while the rest engaged in farming. This was the only way to meet the State’s plans.

If you convert the necessary amount of food for living to grains, one would need 150~160 kg of grain per year. However, a farm member couldn’t even taste a single grain. That’s because after the harvest was taken away for military provisions, all that was left were potatoes. In other words, the farmers could only get potatoes, and even then, the maximum amount I received was about two months’ worth. For the remaining ten months of the year, I had to manage on my own.

The farm members had no reason to work hard. They had toiled for a long time for the sake of the country but their mindset changed because they received so little in return. The law might try to control the people but what can it do when the people are starving? People now resist, saying, ‘I simply can’t work anymore.’ However, the collective farm grants no leniency to its members. The farm must adhere to the law. Instead, the State turned a blind eye to individuals cultivating small private fields. The State is aware that even after a year of labor, a farm member ends up with only two months’ worth of food. They have to make people work, but people refuse because they have nothing to eat. Physical beating or disciplinary labor camps wouldn’t solve the problem. Hence, private fields proliferated naturally. It was the only way for farmers to supplement their food for the remaining ten months, with very few to spare. Although far from satisfactory, it prevented them from starving.

Name: Kang-hun(pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1990s

Gender: Male

Hometown: Kimjongsuk County, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Soldier

Year of Escape From North Korea: 2018

Farm members wish to leave the farm because most of their hard-earned harvests are offered to the State. Although there have recently been numerous cases of individual farming, North Korea still operates under a collective farm system. For example, if there are a few jongbo(1 jongbo = 9,917.4㎡)s of land, the government stipulates a required harvest rate. For instance, one jongbo of land has to produce at least 8 tons of rice. Consequently, the members have to toil. However, in reality, the government does not adequately support or compensate for farming materials such as fertilizers or agricultural equipment. While there is some support, it is far from enough. Without sufficient fertilizers, the harvest is bound to be poor. Therefore, farmers must purchase additional equipment or fertilizers, either by paying for them on their own or borrowing money. Then what happens after the harvest? Doesn’t the farmer have to pay back his debts? Then, a chunk of his harvest is gone.

The government collects rice for military provisions as a matter of priority in rural areas. Soldiers come and collect them. The government set it that way. It dictates, ‘You must provide this amount of food to this military unit this year,’ and the farmers are obliged to comply without question, even during spring and summer when they need to feed themselves. Consequently, those who grow crops are the ones who starve the most. Although the State provides rationing, it only lasts for two or three months. For the remaining nine or ten months, people have nothing to eat. Therefore, farmers resort to cultivating personal fields in the mountains. All farm members strive to escape the struggles of rural life.

Name: Ko Hye-myong(pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1980s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Pochon County, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Lumbermill Worker

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

Farm members do not grow crops on their own land but on State-owned land. They receive a portion of the harvest in return. To be honest, as North Koreans know very well, they work hard on their own crops because they are all theirs, but who would work hard on the State’s land as if it were their own? Naturally, state-owned land yields poor harvests, which makes it difficult for farm members to make a living working on State farms.

A few clever members are better off because they also cultivate their own personal fields. The crops from personal fields belong entirely to them, whereas those from collective fields are distributed among all members since it is a communal harvest from communal land. However, one ton of potatoes for a household with four members is not sufficient. Each person needs at least one ton, meaning 4 tons are required for a household of four. But the collective farm or the State only provides one ton for a family. Then, how can other members feed themselves? After the autumn harvest, people get by for a season. But the potatoes run out by March or April the following year.

Name: Gong Na-jong(pseudonym)

, Year of Birth: 1970s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Tanchon City, North Hamgyong Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Librarian

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2018

The collective farm provides its members with seeds, fertilizers, water, and other necessities. Then the members produce crops from the land they are responsible for. They give a portion of the produce and keep the remaining. However, if I failed to meet this year’s production plan, I would still have to meet the quota, even if that means buying additional produce. This way, the State loses nothing. In the past, the state distributed the harvest to the members and then took the remaining, regardless of the harvest quality. But now, the State takes its share first. The State suffers no loss, and all the loss falls on the members. That’s why farm members have hard times. They resort to raising cattle, brewing alcohol, or engaging in merchandise activities in winter when they don’t work for the farm. With no distribution or rationing, and no harvest of their own, they have to find alternative ways to survive.

Name: Kim Kyong-rae(pseudonym)

, Year of Birth: 1980s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Manpo City, Chagang Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Unknown

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

There are vast plains in North and South Pyongan Provinces. The produce from these regions is to be distributed to each munitions factory in autumn. Workers from the factories drove from rice field to rice field, crop field to crop field, collecting rice and crops on site. They even threshed the crops themselves and took them, distributing and consuming the food themselves. This was essentially seizing what belonged to the farm members. I lived near a munitions factory and worked there when I was young. I saw how they collected crops from the rural area. Police officers would enter farm members’ houses and search every corner to check for anything they could take away. They took away food the farmers needed to feed themselves. Despite this, residents in the area found ways to make a living by any means necessary, such as by engaging in merchandise activities. They survived, despite receiving nothing from the State.

Name: Lee Won-ho(pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1960s

Gender: Male

Hometown: Wonsan City, Kangwon Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Local Retailer

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2017

Farm members don’t ‘offer’ the harvest to the State. The word ‘offer’ is incorrect. Since the land does not belong to the farm member, the produce is not his, is it? He is only a worker cultivating the state-owned land. It is not a structure where he has to offer his own produce from his land to the State.

My relative was also a farm member. In his case, he received no money and there was no rationing, except for some rice. Consequently, he had to resort to stealing. During the autumn harvest season, he would steal the rice he needs for himself . Threshing typically took place at night, so he would sneak into the rice mill and take enough rice for his family to last a year. Otherwise, by the following March or April, they would have nothing to eat except for digging up grass roots. Since the harvest often fell below the target amount, if one was supposed to receive 100 kg of rice per person per year, they got less than 50 kg.

Name: Kim Min-ok(pseudonym)

, Year of Birth: 1960s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Pochon County, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Farmer

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

I was a farm member. The state dictated that a farmer’s children were to work on collective farms and a miner’s children were to work in mines. In other words, children followed their parents’ occupation from generation to generation. This restriction was most strict for farm members, the most fundamental occupation.

Even when I was in North Korea, if you grew crops for six months, you could barely eat for four months. But now, all the borders are shut down. Due to the poor soil, a plentiful supply of fertilizers from China was necessary for farming. Now, without them, the harvest would be lower. When I lived in an area near the North Korean-Chinese border, I planted corn seeds from China. The farmers there would not be able to get seeds from China now. I worry about North Korean agriculture.

In rural areas, if you are a farm member, your spouse is supposed to work at the farm as well. The farm members have to survive somehow and they resort to usury as one means. What that means is that you lend 1kg during the spring lean season, and collect 2kg in autumn. Those who are better off are able to practice such usury.

NO FREEDOM OF RELIGION

There is no freedom of religion in North Korea. No religious activities, including those related to Christianity and Buddhism, are permitted. Religious institutions and individuals in certain parts of North Korea primarily exist for the sake of appearances to the outside world. In short, North Korea limits all forms of religious practices.

North Korea’s Constitution guarantees the people’s “freedom of religion.” The Socialist Constitution Article 68 stipulates that “Citizens have freedom of religious belief. This right is granted through the approval of the construction of religious buildings and the holding of religious ceremonies.” This is merely a legal provision and, in reality, religious freedom is not guaranteed.

On the contrary, a believer of religion faces a severe punishment. In North Korea, the Kim family is virtually God. Therefore, having a religion is equivalent to committing treason. Therefore, those who are caught for having a religion can face the death penalty, beyond imprisonment, or they could be sent to a political prisoner camp.

Most North Korean people are unaware of what religion is or what kinds of religions are there. To them, religion is simply a bad thing that they must not believe.

The followings are a compilation of testimonies from several people who left North Korea regarding the perception of religion in North Korea. Through this, we can infer the reality of religious freedom within North Korea.

Name: Song Woo-il (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 1990s

Gender: Male

Hometown: Pochon County, Ryanggang Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Train Engineer’s Assistant

Year of Escape from North Korea: 2019

People don’t know whether there are Catholicism or Buddhism. Buddhism, for example, people know that it has been around from the past, but that’s about it. There are temples. There are a few of them, but I’m not sure if there are monks present. The county has used them to earn money from historical site tourism, or they might have kept them for historical conservation. But there seemed to be no monks there. Things like having your head shaved and living as a monk are not allowed. I’ve heard about churches before, that there was a church somewhere in Pyongyang. Ah, I meant a cathedral, not a church. I heard that there was one for the sake of formalities. Even if there was a church in North Korea, people couldn’t have gone there. That would be illegal. Imagine you have a 10-year-old child, and you tell them, ‘Don’t do this and that.’ The child wouldn’t do it, would they? In the same way, the Ministry of State Security conducts a so-called ‘Political Doctrine.’ They give presentations once or twice a year to elementary school students, beginning from the first or second grade, and tell them what things are not allowed. They would show the Bible and say, ‘This is a tool to dismantle our Republic, used by the South Korean puppets.’ With the hatred implanted from an early age, the kids naturally think of the Bible as something bad. When I was in North Korea, I wondered why people with the Bible were taken away. The question always lingered, but I couldn’t get an answer because I never had a chance to actually read one. In South Korea, I realized that the thick, brown book I had seen in one of the presentations was a Bible. I think now that they didn’t allow us to read the Bible because they thought people might start having beliefs in the church and not listen to what they say.

Name: Jang Yon-ju (pseudonym)

Year of Birth: 2000s

Gender: Female

Hometown: Chongjin City, North Hamgyong Province, North Korea

Occupation in North Korea: Unemployed

Year of Escape From North Korea: 2019

It was around 2017 or 2018 when there was an execution related to things like God or Christianity. (Translator’s note: the word ‘God’ is a translation of Hananim. The word Hananim is used also in South Korea specifically denoting the Christian God.) At that time, I didn’t know about Christianity, but apparently, there was a woman in Cheongjin or somewhere who claimed that she was God, lured teenagers, and made them worship her. She was caught and publicly executed, and her follower-teenagers were sent away somewhere. I didn’t see the execution myself. I heard she was shot. In North Korea, people must attend public executions. Even your workplace tells you to go. But I was a student then, and students were exempted from seeing one. The state does not send students to public executions.